Deep Dive: India Rising Part 2—E-Commerce Disruptors in India

KEY POINTS

This is the second report in our India Rising series focusing on the Indian startup ecosystem. We identify the following four retailers as the main disruptors in Indian e-commerce: Flipkart, Snapdeal, Quikr and Bigbasket. There are five primary factors that have shaped the Indian e-commerce sector:

- A paucity of modern retail stores has boosted demand for products and brands sold online.

- Strongly price-competitive e-commerce marketplaces are well positioned to attract shoppers with limited incomes, who constitute a large part of India’s consumer population.

- Offering cash on delivery (COD) as a payment option allows more Indian consumers to buy online.

- India has one of the world’s largest Internet user bases, and Indian consumers’ disposable incomes are increasing.

- Government restrictions on foreign investment in India’s retail sector and Amazon’s and Alibaba’s relatively late entries in the country have helped domestic startups gain a strong foothold.

Executive Summary

This is the second report in our India Rising series, which looks at the startup ecosystem in India. In this report, we examine four companies that are significant disruptors in Indian e-commerce—Flipkart, Snapdeal, Quikr and Bigbasket—and identify five factors that have shaped e-commerce in the country:

- A paucity of modern retail stores has boosted demand for products and brands sold online. Total sales made through modern retail channels are very low in India, and the country ranks lowest in terms of modernization of the retail industry and international trade among major developed nations and the other BRIC countries, according to Knight Frank Global Research.

- Despite the fact that India’s economy is growing, many consumers in the country have limited incomes. Strongly price-competitive e-commerce marketplaces are well positioned to attract Indian shoppers.

- Many Indian e-commerce sites offer a cash-on-delivery (COD) payment option, enabling more shoppers to buy online in a country where more than two-thirds of transactions are made in cash.

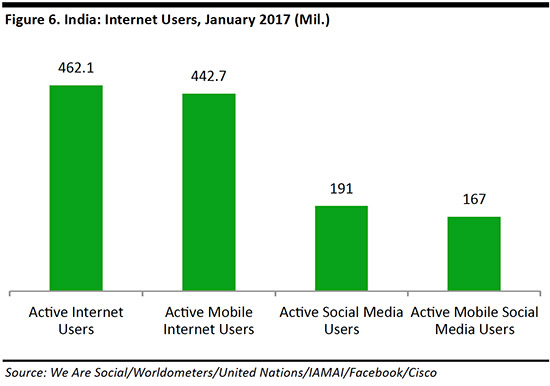

- India has one of the largest Internet user bases in the world; some 462.1 million people accessed the Internet in the country in January 2017. A growing population of young Internet users with increasing disposable incomes has contributed to the growth of the four companies we profile in this report.

- Government restrictions on foreign direct investment (FDI) in India’s retail sector and Amazon’s relatively late entry in the country helped domestic startups gain a strong foothold.

Amazon is a major new threat to domestic e-commerce operators in India. The US giant has been expanding its offering into new categories and is now trying to muscle in on the grocery market. With nearly a third of consumer spending in India dedicated to food, Amazon is looking at a very lucrative grocery market in the country. Recently, Alibaba also clearly indicated that it is ready to compete for market share in the Indian online retail sector.

Unless homegrown rivals provide truly innovative offerings rather than just attempting to grab market share with promotional deals during festive periods, there will be little stopping Amazon from stealing share from local players.

An Introduction to Retail and E-Commerce in India

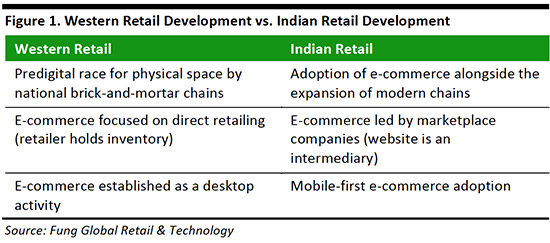

Offline retail is much less developed in India than it is in Western countries. Yet there is no shortage of tech-driven disruptors bringing more choice, greater convenience and lower prices to Indian consumers through e-commerce. In fact, rather like China, India seems to be almost leapfrogging the intermediary stages of retail and e-commerce development and moving directly toward mobile-centered, marketplace-focused retailing.

The country appears to be skipping over the retail stages seen in the US and Europe, where leading national chains emerged by establishing as much physical retail space as possible and where e-commerce was subsequently established through desktop shopping at retailers’ websites. The table below illustrates our view of how India is shortcutting the traditional model of retail evolution.

In this report, the second in our India Rising series, which looks at the startup ecosystem in India, we examine four companies that are major disrupters in Indian e-commerce—Flipkart, Snapdeal, Quikr and Bigbasket. We consider the factors that shaped e-commerce in India and we look at why these companies have been particularly successful.

E-commerce is the subject of our next report in this series, too. The emergence and exponential growth of e-commerce in India has led to the development of ancillary firms, such as IT solutions providers and courier delivery businesses, that support the various functions of online retail. These “e-commerce enablers” are the subject of the third report in this series, which we will publish shortly.

The first report in this series looked at the factors that make India a burgeoning startup destination, the top startups by funding, the main accelerators, the major investors and the role of the government. Readers can find that report on our website.

Here, we first look at the size of India’s retail and e-commerce sectors and some of the key factors that shaped e-commerce in the country and paved the way for the disruptors we outline later.

Retail and E-Commerce in India

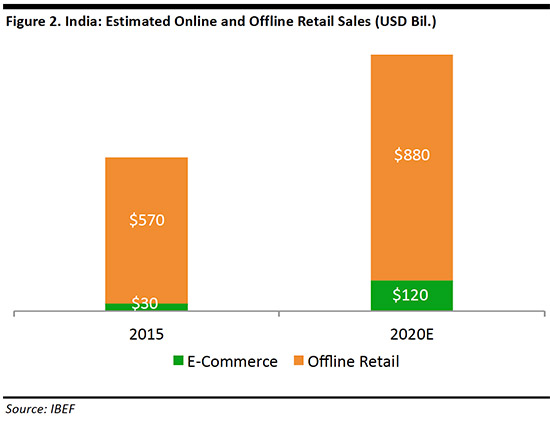

India is the world’s second-largest country by population and it has the fourth-fastest-growing economy. Its retail market was worth some $600 billion in 2015, according to the India Brand Equity Foundation (IBEF), and it is expected to touch $1 trillion by 2020. E-commerce accounted for 5% of Indian retail in 2015, equivalent to $30 billion. That share is expected to grow to 12%, or about $120 billion, in 2020, according to the IBEF.

Factors that Have Shaped E-Commerce in India

Several factors unique to India have helped shape e-commerce in the country:

1. Lack of Modern Infrastructure

A paucity of modern retail stores in India has boosted demand for products and brands sold online. The Indian retail industry is overwhelmingly unorganized (i.e., traditional) and highly fragmented, with the majority of the Indian population buying from informal retail channels such as tiny kirana stores. This means that a very large portion of the country’s retail sector remains to be captured by modern retailers.

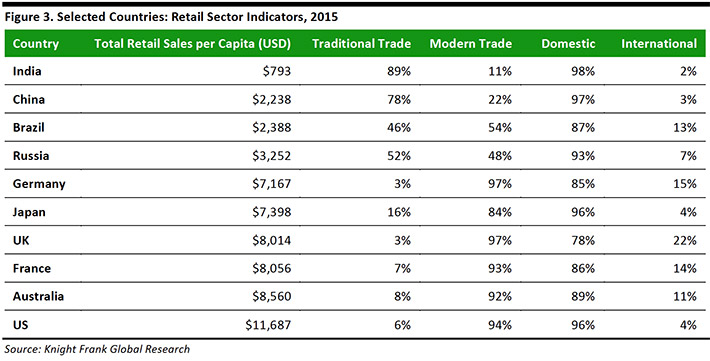

Despite the size and economic growth of India, mall and modern store penetration is still low. Various estimates suggest that organized retail (modern trade) constitutes only 6%–8% of total retail in India. Sales per capita that are made through modern retail formats totaled just $793 in 2015, while those same sales in each of the other major emerging markets—Brazil, Russia and China (which together with India constitute the BRIC nations)—totaled at least a few thousand dollars. Among the countries listed in the table below, which includes the BRIC nations and major developed markets, India also ranks the lowest in terms of modernization of the retail industry (as represented by e-commerce), shop units and shopping malls (compared with bazaars and markets in traditional trade), and in international trade.

The paucity of modern physical retail formats in India meant that consumers were a ready market for e-commerce players: shoppers flocked to sites such as Flipkart and Snapdeal to buy products and brands that were not easily accessible in physical stores. People from even the remotest areas are now able to shop for modern products and international brands at the click of a button, and increased mobile and Internet penetration has helped boost e-commerce retailers in the country further.

2. Less-Affluent Consumers Look for Low Prices

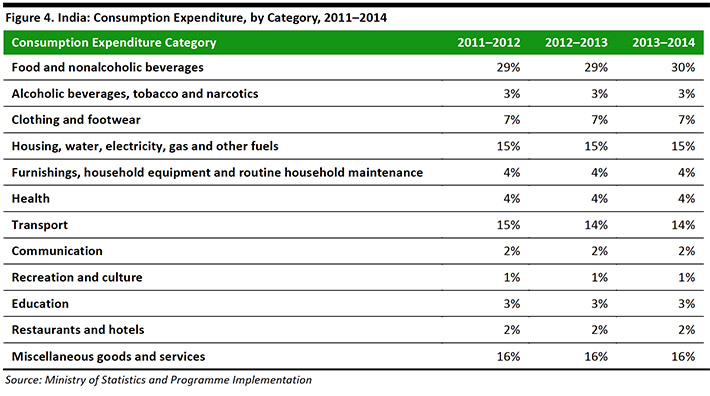

Even with the economy growing, many Indian consumers still have only limited incomes, which spurs demand for low-price marketplaces. It is a general rule that consumers in less economically developed countries direct a greater share of their spending to basic retail categories than do consumers in more economically developed countries. And, as we show in the table below, food and beverages accounted for 33% of Indians’ total consumer spending on various major categories in 2014 (latest). By comparison, food and beverages accounted for just 7% of Americans’ consumer spending on major categories in 2016.

The average Indian has little left over to spend on discretionary items each year: leisure goods and services (listed as “recreation and culture” in the table below) capture only a tiny share of Indians’ total consumer spending.

E-commerce marketplaces that offer both low prices and the ability to compare prices resonate with less-affluent shoppers. For many, it is a necessity to shop for the lowest prices on discretionary goods. Reflecting this, the electronics category has a strong presence online: at the end of 2014, mobile phones and related accessories contributed fully 41% of all online sales in India, according to the Internet and Mobile Association of India (IAMAI). The organization also noted that other major electronics items and apparel accounted for most of the remainder of online spending. This kind of demand boosts traffic and sales on value-driven marketplaces such Flipkart and Snapdeal and on classifieds website Quikr.

3. The Option of Using COD as a Payment Method in Cash-Centric India

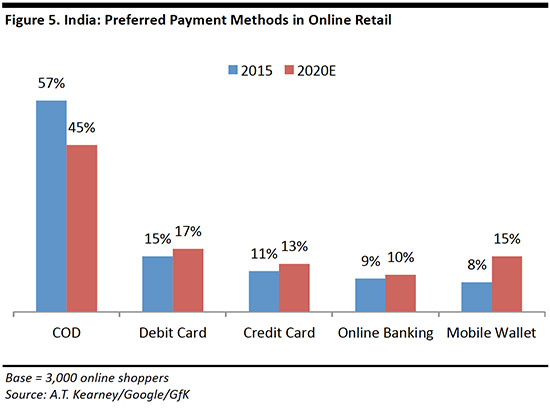

India is a cash-centric economy where some 68% of transactions are made with cash, according to brokerage firm CLSA. World Bank data indicate that bank account penetration in India was only 53% in 2014. COD payment allows more shoppers to buy online and is a fundamental feature of e-commerce retail in India. A 2015 survey by A.T. Kearney, Google and GfK found that 57% of online shoppers in India cited COD as their preferred payment option. That percentage is forecast to decline to 45% by 2020, when 15% of shoppers are expected to prefer to make payments through mobile wallets, an option preferred by only 8% of those surveyed in 2015.

4. The Scale and Youth of the Internet User Base Boosts E-Commerce

The sheer size and youthfulness of the Indian Internet user and shopper base has also powered growth at e-commerce startups. India has one of the largest Internet user bases in the world: according to brand agency We Are Social, some 462.1 million Indians accessed the Internet in January 2017. But in terms of Internet penetration, the country ranks low, as this base constitutes only about 25% of India’s 2016 population.

Low income levels have also made high-tech, expensive gadgets that provide access to the Internet unaffordable in India. This has led to the majority of the user base accessing the Internet through smartphones. Mobile Internet users represent fully 96% of total Internet users in the country.

Flipkart and Snapdeal have sought to cater to these consumers with faster-loading mobile versions of their websites and with mobile apps. Lately, more retailers have been investing in enhancing their mobile capabilities in order to attract shoppers who rely on smartphones.

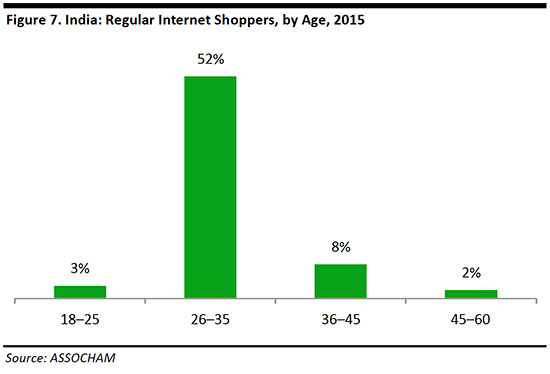

The Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India, known as ASSOCHAM, reports that India had one of the youngest Internet user bases among the BRIC nations in 2015, with about 52% of those online being between the ages of 26 and 35.

A growing young and tech-savvy population with increasing disposable incomes welcomed the choice and convenience that e-commerce sites such as Flipkart, Snapdeal, Quikr and Bigbasket provided. The four firms also made strategic moves that appealed to young consumers, and these were key to the firms’ growth. One example is Flipkart’s acquisition of online fashion retailer Myntra, which offers fast-fashion Western clothing brands that are hard to come by at local apparel stores in India. Another example is Quikr’s advertising, which has effectively conveyed the convenience the site offers to those who want to buy or sell used goods, thereby capturing the attention of young, urban Indians.

5. FDI Restrictions and the Relatively Late Entry of Amazon in India

Domestic disruptors have benefited from government policies that restricted FDI in Indian retail. The government of India operated a somewhat closed economy until the last decade or so. In 2006, it undertook one of its first moves to open up the economy and implemented a policy that allowed FDI of up to 51% in single-brand retail, subject to government approval. This meant that retailers such as Gap and Zara, which sold only their own-brand products, were allowed to open shops in partnership with a local company in India, with a maximum ownership stake of 51%.

In 2012, the government removed this cap and increased the permissible investment by a foreign entity in single-brand retail to 100%. In addition, it allowed FDI of up to 51% in multibrand retail (which includes department stores and supermarkets that stock and sell products of various brands), subject to government approval. Marketplace sites were effectively exempted because FDI was permitted in business-to-business e-commerce, and marketplaces are technically technology platforms that facilitate trade between buyers and sellers. This helped existing e-commerce marketplaces in India raise larger amounts of foreign funding, thus making the marketplace the predominant business model for online retail and paving the way for Amazon to operate a marketplace using domestic sellers in India beginning in 2013.

In 2016, the government indicated that it will allow 100% FDI in food-only retail as long as the food is produced and packaged in India. However, retailers still need clarification from the government on this, as most grocers tend to sell nonfood products as well as food.

In the next section, we profile the notable disruptors in Indian e-commerce and examine some of the reasons for their success.

Notable Disruptors in Indian E-Commerce

We focus our analysis on the four e-commerce companies that have received the greatest funding: Flipkart, Snapdeal, Quikr and Bigbasket. E-commerce marketplaces Flipkart and Snapdeal have proved hugely popular; Amazon and these two firms comprise the three most-visited shopping websites in India, according to a 2015 survey by MasterCard.

Flipkar

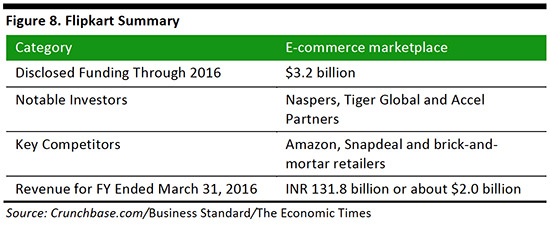

Privately held Flipkart was established as an online book retailer in 2007 by former Amazon employees Sachin Bansal and Binny Bansal, with initial startup capital of approximately $6,000. Nearly a decade later, it has become the undisputed homegrown leader in Indian e-commerce. Morgan Stanley valued the company at a sizable $5.6 billion as of November 29, 2016, although that figure was down from a peak valuation of $15.2 billion in 2015. The company attained “unicorn” status in 2012, when it raised some $150 million through a funding round led by South African Internet company Naspers.

What Made Flipkart Successful?

Known for flash sales, heavy discounts and attractive deals during festive seasons, Flipkart has made strategic acquisitions of specialist Internet retailers such as Myntra in order to bolster its market position and, in doing so, has proved a worthy competitor to global online retail giant Amazon. However, while Amazon and other leading pure plays in the West started with traditional direct-retailing models (meaning they owned the stock they were selling), Flipkart launched with a consignment format. It procured stock on demand, based on the orders it received, and sold that to its customers. Flipkart later implemented the inventory model (i.e., it began holding the stock it sold) and now operates as an e-commerce marketplace. Like global players such as Alibaba Group, Flipkart does not own the inventory sold via its platform.

In its 10 years of existence, Flipkart has had a turbulent financial journey. Losses swelled until its March 31, 2015, fiscal year-end. The company finally posted a recovery in its most recent financial year, with revenues of INR 131.8 billion, or $2.0 billion (a year-over-year increase of nearly 43%), and a net loss of INR 5.4 billion, or $79.8 million (a decrease of some 38%), according to a report by Indian newspaper Business Standard.

Due to its marketplace format, Flipkart’s reported revenues are not a direct indicator of the value of goods sold on its site—for that, we look at gross merchandise value (GMV). In March 2014, Flipkart’s GMV was estimated to be approximately $4 billion, and the company noted that it aimed to achieve $10–$12 in billion in GMV over the next 12 months. But the company announced in May 2016 that it was going to stop disclosing GMV and replace the metric with its net promoter score, which is used to measure customer loyalty.

In January 2017, Kalyan Krishnamurthy, a former senior executive at Flipkart investor Tiger Global, was appointed CEO of Flipkart. This was seen as unusual, as founders of Indian startups seldom concede power to an outsider. We expect Flipkart to make more such pragmatic decisions, even if it means bucking the trend, as it fights to retain a leading market position.

Flipkart faces new threats from Amazon, which is growing market share, and from Alibaba’s recent advances into Indian e-commerce via the newly spun-off Paytm Mall, a marketplace that was formerly part of India’s largest mobile wallet, Paytm. To counter these challenges, Flipkart is reportedly seeking funding of $1.5 billion from marketplace eBay and Tencent, the owner of messaging app WeChat. The funds would provide Flipkart a much-needed stimulus that would give it a strong footing in the market.

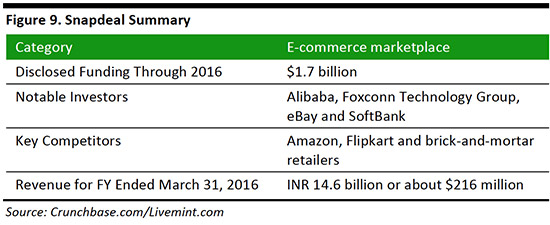

Snapdeal

Snapdeal is India’s second-biggest e-commerce player—and, tellingly, like Flipkart, it is a marketplace rather than a retailer. Snapdeal was established in 2010 and has received enormous amounts of funding from many prominent investors, including Alibaba, SoftBank and eBay.

What Made Snapdeal Succesful?

Similar to Flipkart and Amazon, Snapdeal runs flash sales, deals of the day and sales during holiday seasons. Snapdeal has made a number of acquisitions, including an online marketplace for designer handmade goods called Shopo (which ceased operations on February 10, 2017) and digital payments app Freecharge.

Snapdeal achieved early success because it launched as a marketplace and did not experiment with other business models. As one of the first companies to pioneer a business model that few online retailers in India used, Snapdeal provided greater choice to consumers than Flipkart and other e-commerce companies did, which helped it garner a substantial share of the market. It also used third-party vendors to fulfill business functions, such as logistics and delivery, instead of setting up all business functions in-house. This helped it focus the majority of its resources on its marketplace.

Challenges Snapdeal Faced

Despite being a market leader and garnering the attention of large international companies, Snapdeal’s net loss in the year ended March 31, 2016, swelled by 150% year over year, to INR 33.2 billion, or $490.8 million. The loss was more than twice the revenue it generated during the period, which totaled INR 14.6 billion, or $216 million.

Though Snapdeal did not disclose GMV figures, people familiar with the firm told financial newspaper Livemint that Snapdeal’s GMV would have amounted to about $2 billion in March 2016. In April 2016, Snapdeal’s CEO, Kunal Bahl, announced that the firm would not give out official estimates for the metric (Snapdeal rival Flipkart soon thereafter made the decision to not announce its own GMV).

In a February 2017 interview with the Reuters news agency, Bahl acknowledged that the Indian market is intensely competitive and that it is dominated by Amazon and Flipkart. He added that Snapdeal could potentially make a profit in two years, as it is resolutely working to drive down costs and increase efficiency.

Recent Developments

Just days after that interview with Reuters, Snapdeal announced that it would lay off hundreds of its employees. The firm has also seen many top-level exits over the last six months. In a letter addressed to employees, both Bahl and the company’s cofounder admitted to making “mistakes” and said that they would each “take a 100% salary cut.”

The firm hopes to raise fresh funding from investors as it struggles to pay the more than $180,000 it owes vendors.

- For further discussion of global e-commerce marketplaces that are disrupting retail, please see our earlier report on the topic on our website.

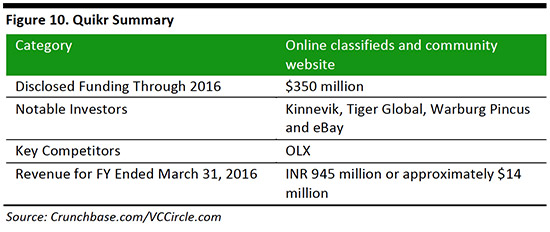

Quikr

Quikr was one of the first websites in India to function as an online classifieds platform connecting local buyers and sellers across various categories. It was established in 2008 and has attracted funding from Kinnevik and Tiger Global, which are its largest investors, as well as from Warburg Pincus and eBay.

What Made Quikr Succesful?

To strengthen its position, Quikr has made several strategic acquisitions, the main ones being Stepni, which connects vehicle owners with service providers; Grabhouse, a home rental firm; and ZapLuk and Salosa, which are beauty and wellness services providers.

Challenges Quikr Faced

Despite posting revenue growth of 44% in its 2016 fiscal year, when revenue reached INR 945 million, or $14.0 million, Quikr’s losses grew by 20%, to INR 5.3 billion, or $78.4 million, which was nearly five times its revenue.

In a 2015 funding round led by Tiger Global and Kinnevik, Quikr raised over $150 million, but it has still not managed to dissipate its losses in the increasingly competitive Indian classifieds space due to the emergence of rivals such as OLX and Craigslist.

Recent Developments

Quikr reported that it doubled its revenue in its fiscal third quarter ended December 31, 2016. In an interview with Forbes in February 2017, CEO Pranay Chulet said that the company’s focus is to strengthen its position and drive financial growth across the verticals in which it operates.

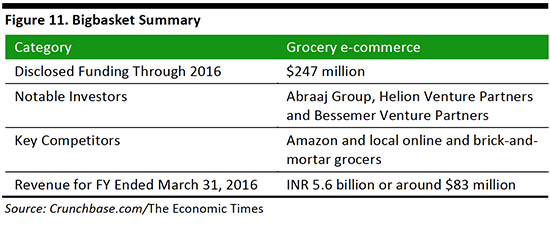

Bigbasket

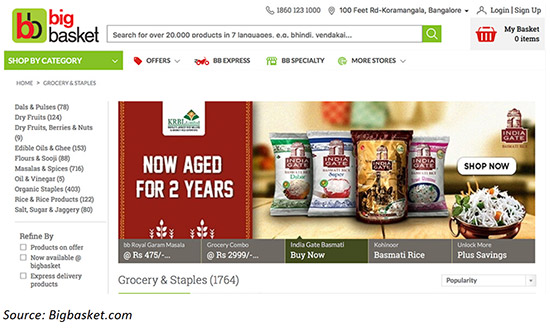

Internet grocery retailer Bigbasket launched in 2011 as one of the first online grocery stores in India. It is now the largest online grocery retailer in the country, and offers some 18,000 products and more than 1,000 brands across nearly 30 of India’s largest cities.

What Made Bigbasket Successful?

A unique feature of the website is that shoppers can look for fresh food and food products using those products’ local or ethnic names, such as bhindi for okra and dal for lentils. Shoppers can also buy products from international brands on the website.

Bigbasket’s operating model sets it apart from Flipkart and Snapdeal. It is not a marketplace, which means it owns its inventory, warehouses and delivery fleet.

To get around the FDI restrictions in direct online retail and the inventory-led e-commerce model, the owner of the Bigbasket brand, Supermarket Grocery Supplies, sources the products and sells them to Innovative Retail Concepts, the company that is responsible for the website, logistics and delivery. So, in effect, the business-to-business firm Supermarket Grocery Supplies, rather than the business-to-consumer company Innovative Retail Concepts, receives investment from foreign firms.

According to The Economic Times, Bigbasket reported revenues of INR 5.6 billion, or $82.8 million, in fiscal year 2016, almost triple its revenues from the year before. However, the company’s losses quadrupled year over year, to INR 2.8 billion, or $41.4 million, which CEO and Cofounder Hari Menon attributed to increased operating costs, investments in mobile apps and building warehouses in the cities in which the firm operates. Cofounder Vipul Parekh told the press that the firm hopes to triple its revenues to INR 20 billion, or $296.0 million, in fiscal 2017.

Challenges Bigbasket Faced

In an interview with Livemint in October 2016, Menon said that one of the challenges the company faces is employee retention, as it employs more than 12,000 people, two-thirds of which work in blue-collar roles. Menon said that Bigbasket has instituted a trust fund that supports the workers’ families in order to provide an incentive for workers to remain with the company.

Recent Developments

Bigbasket recently announced that it has plans to expand its private-label mix to include nonfood products. Its private-label portfolio currently contributes 33% of the company’s total revenue, according to startup news website VCCircle.com, and the firm hopes to push this up to 45% by the end of the current fiscal year.

Following the government’s indication last year that it will allow 100% FDI in food retail, Bigbasket is seeking approval for FDI in direct-to-consumer food retail, as are Amazon and Indian e-grocer Grofers.

Homegrown online retailers had a satisfactory run until last year, but it seems like the e-commerce sector in India is set to undergo a sea change over the next few months. In the following section, we outline the evolution of India’s protectionist regime into a more open retail market and examine how this helped domestic retailers, and then discuss the threat implied by Amazon and Alibaba as the market opened up.

The Indian E-Commerce Bubble and the Rising Threat from Amazon and Alibaba

Government restrictions on FDI in Indian companies in selected sectors constrained non-Indian retailers from selling directly to consumers. As we discussed earlier, prior to 2012, FDI was forbidden in multibrand retail. After 2012, foreign ownership was limited to a maximum 51% of such firms.

Having a marketplace model helped firms such as Flipkart and Snapdeal attract large amounts of funding from foreign investors and allowed foreign retailers to sell through their platforms. Non-Indian retailers were not permitted to sell directly through e-commerce, even if they had invested in physical stores in the country through the FDI route. However, marketplace sites were effectively exempted through a loophole that allowed FDI in business-to-business e-commerce, and this contributed to their growth. Until the liberalization of FDI rules in 2012, direct-retail websites that competed with marketplaces would not have been able to attract foreign investment.

When Flipkart was established in 2007, it faced few direct rivals—and most of those did not evolve with consumer needs and eventually closed down. Snapdeal entered the market in 2010 with a highly promotional sales strategy that included attractive deals and deep discounts across numerous categories, something that many of its online retail rivals did not offer at the time.

Similarly, Quikr did not have any competitors of the same scale when it launched; its main competitors were newspapers that ran classified advertisements. Meanwhile, Bigbasket was the first online grocery retailer that thrived while others failed. It was successful to the extent that it expanded to serve many cities across India at a time when modern, large-format supermarkets were still new in the country.

The relative absence of competition allowed these four companies to establish themselves as the dominant players in their respective sectors.

Amazon’s late entry into India and the limitations it faced due to government policy allowed homegrown e-commerce retailers in the country to establish themselves, but it appears that they underestimated the threat posed by the global giant in their domestic market.

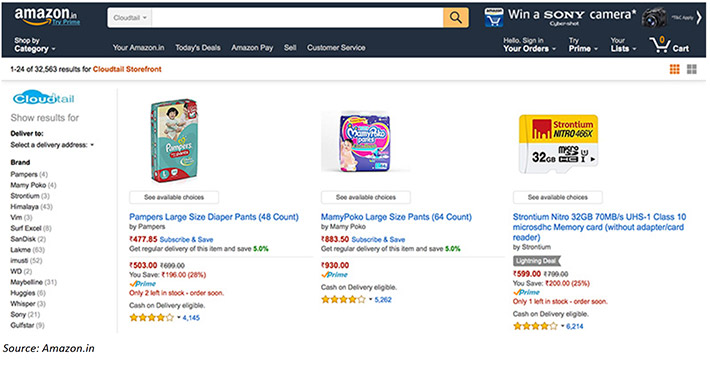

Amazon worked around FDI restrictions through complex joint venture structures with local players. One such venture with Indian technology firm Infosys formed an electronics and fashion vendor called Cloudtail that is the largest seller on Amazon’s Indian platform. Thus, Amazon manages to be both a marketplace and a seller in India. The company has undertaken many such strategic moves, the latest of which was applying for government approval to sell food online in India.

Given Amazon’s global scale of operations, its expertise and its strong capital base, it did not have to strive for very long before overtaking domestic rivals and becoming one of the leading players in Indian e-commerce.

The ambitions of global rival Alibaba were less clear, as it held only minority stakes in Snapdeal and Paytm until recently. In February 2017, it invested some $177 million in Paytm Mall, taking its stake in the firm to over 60% and signaling its readiness to contend for a leading share in Indian e-commerce.

Unless they possess the breadth of operations that Amazon and Alibaba do, most e-commerce marketplaces that compete to retain customers through deep discounts and attractive deals tend to struggle to sustain the strategy in the long run.

What We Think

In this report, we have noted the tailwinds that have benefited major domestic online players in India. The success of these firms and the growth of e-commerce in general have also been helped by the expansion of firms that provide supplementary services. Those companies are the focus of the next report in this series.

For the business-to-consumer e-commerce firms we focused on in this report, an easing of restrictions on FDI and Amazon’s and Alibaba’s efforts to claim greater share of the Indian market mean that there are new threats to face. While Alibaba has publicly indicated its eagerness to gain share only recently, Amazon has gradually been expanding its offering into new categories and is now trying to muscle in on the Indian grocery market. With nearly a third of consumer spending in India dedicated to food, Amazon is looking at a very lucrative grocery market in the country.

In order to head off the threat from the major global players, domestic e-commerce companies have made a number of strategic moves, including running a spate of discounts and deals, making acquisitions, and spinning off unviable divisions. Meanwhile, Amazon faces challenges in terms of being a foreign company that is still finding its footing in culture-sensitive India.

Amazon recently faced controversy when its Canadian site featured a doormat for sale that resembled the Indian flag. Many Indian shoppers took offense, and the government eventually intervened. Such missteps may temporarily mar the retailer’s growth trajectory. However, as long as Amazon deals with Indian cultural issues with sensitivity and swiftness, there is little to stop it from stealing share from local players.

To maintain their standing, domestic rivals must provide truly innovative offerings or forge strategic partnerships rather than just attempting to outpace each other with promotional deals during holiday periods.

The major Indian e-commerce disruptors have enjoyed tremendous success—but it looks like the disruptors are about to be disrupted.