Turkey Retail Overview: Characteristics, Developments and Prospects

KEY POINTS

This is the third in our series of reports looking at retail trends in major economies.

- Turkey presents something of a contradiction to international retailers looking for growth markets to tap:

- On paper, macro factors, such as economic expansion, a growing and young population, strong retail sales growth, and a fragmented retail sector, bode well for modern, international retailers.

- Yet, in practice, distinct national shopping preferences and a less-than-transparent regulatory regime have worked against a number of international retail entrants. Recent events have added a backdrop of uncertainty that is likely to persist.

This is the third report in our series looking at retail trends in major countries. Our first report discussed Germany and our second report covered France.

Turkey presents something of a contradiction to international retailers looking for growth markets to tap. Macro factors at work in the country, such as economic expansion, a growing and young population, strong retail sales growth, and a fragmented retail sector, bode well, in theory, for sophisticated retailers. They could benefit from growth and consolidation opportunities in the country.

Yet distinct shopping preferences and a less-than-transparent regulatory regime have worked against some international retail entrants. Moreover, recent domestic troubles, including terrorism and the attempted coup in July 2016 have created a backdrop of uncertainty that is likely to persist. This dichotomy is at the heart of our coverage.

The first section of this report focuses on the retail sector and discusses the following themes:

- Domestic retailers lead a relatively fragmented industry. The discounter model operated by BIM has shown a particular ability to meet Turkish consumers’ preference for proximity shopping and lower prices, while international retailers’ focus on larger supermarket formats has shown its limits.

- Domestic companies also lead non-grocery retail sectors: Waikiki leads in apparel, Teknosa in consumer electronics and Hepsiburada in e-commerce.

- As Turkey’s economic growth slowed and its political instability increased, many large international retailers began to disengage from the market beginning in 2013. International fast-fashion chains appear to have been the exception.

- Domestic retailers have been taking advantage of this disengagement, scaling up their businesses by acquiring operations or gaining controlling stakes in joint ventures with international players. One of the most recent examples of this trend is Migros’s acquisition of Kipa from British retailer Tesco in June 2016.

We then place retail in context, with a consideration of key macro indicators, such as economic growth rates and forecast population changes, before turning our attention to recent political instability, with a focus on the impacts of the recent coup attempt.

RETAIL IN FOCUS: A MARKET THAT IS TOUGHER THAN IT LOOKS

In this section, we consider the characteristics of Turkish retail sector. In particular, we emphasize that international retailers have found Turkey a difficult market in which to succeed, despite positive data points on metrics ranging from economic expansion to retail sales.

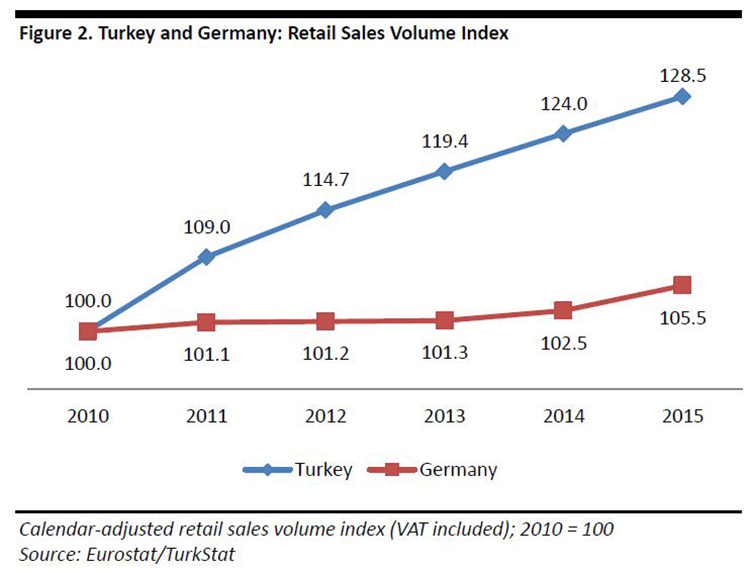

In recent years, the Turkish retail sector has enjoyed buoyant growth. The retail sales volume index for Turkey—which measures inflation-adjusted changes in sector sales—grew by 28.5% from 2010 through 2015. By comparison, the retail sales volume index for Germany increased by only 5.5% during the same period. The total size of the retail sector in Turkey reached an estimated US$303 billion in 2013 (latest), according to Deloitte.

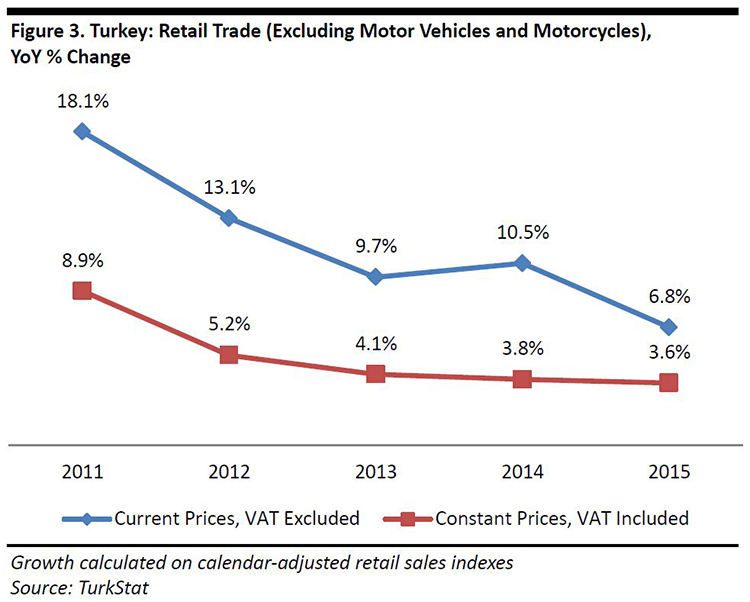

However, the year-over-year increase in retail sales slowed in the period from 2012 through 2015. This reflects a slowing of economic growth and a deterioration in consumer confidence, which we discuss in more detail later. Even with this weakening, annual growth has remained at rates that would be the envy of retailers in Western Europe.

However, the year-over-year increase in retail sales slowed in the period from 2012 through 2015. This reflects a slowing of economic growth and a deterioration in consumer confidence, which we discuss in more detail later. Even with this weakening, annual growth has remained at rates that would be the envy of retailers in Western Europe.

Grocery Dominates Retail

We begin our discussion of retail trends with a look at Turkey’s very substantial grocery sector.

According to the US Department of Agriculture, the grocery sector accounted for 60% of all retail sales in 2015. To place this in context, in the UK food retailers accounted for 45% of all retail sales last year. Deloitte estimates that the total value of grocery retailing in Turkey will reach US$150 billion by 2018.

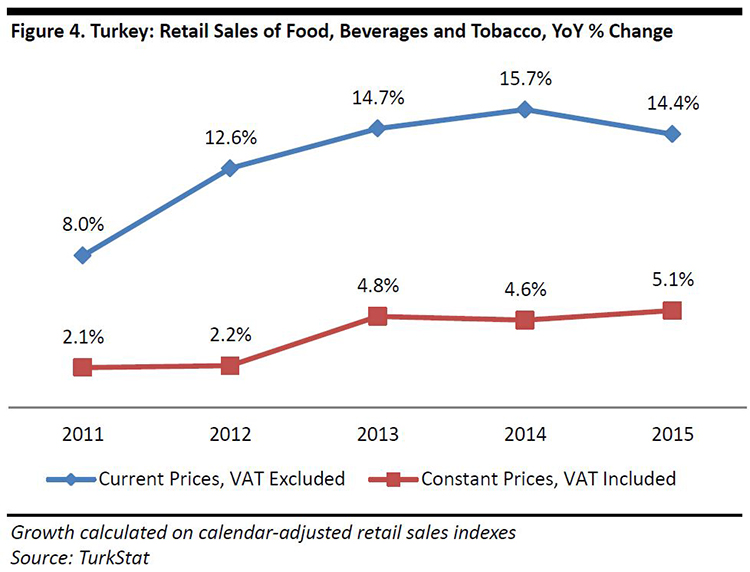

Consumer expenditure on food and nonalcoholic beverages grew at an 11% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) from 2009 through 2014, reaching TRY12 billion (US$5.5 billion) in 2014, according to TurkStat. Turkish consumers kept spending on groceries despite slowing economic growth.

The graph below shows that, in constant prices, grocery sales growth clearly trended upward in the five years through 2015, in contrast with overall retail trade growth, which trended downward in the same period (as shown in the graph above).

Grocery in Turkey: A Challenging Market for Outsiders

Despite being an attractive and growing retail market, Turkey is characterized by three main factors that make it challenging for international retailers to operate in the country: Turkish consumers tend to prefer proximity shopping, the country’s small independent operators are strong and the country’s modern retail sector is fragmented, with strong local players. These factors have also slowed the proliferation of supermarkets and hypermarkets seen in other geographies.

1. Proximity Shopping Is Popular

Despite Turkey’s proximity to the world’s largest oil producers, Turkish consumers pay very high gasoline prices, which discourage unnecessary car rides to out-of-town grocery-shopping destinations. According to the World Bank, in 2014, the pump price for gasoline in Turkey was US$2.06 per liter (US$7.79 per gallon), the sixth-highest price in the world.

Traffic congestion also prevents consumers from moving around easily in Turkish cities. According to the TomTom Traffic Index, which measures the congestion on road networks in 295 cities around the world, Istanbul has the third-highest traffic congestion level in the world.

2. Strong Small Independents

Small independent retailers still retain a large share of the Turkish retail market. According to Global Source Partners, in 2015, such companies accounted for about 40% of the retail sector in Turkey, versus an average of 20% in Europe.

Small independent retailers are particularly strong in the grocery sector, where traditional neighborhood grocery shops, known as “bakkals,” are renowned for their displays of fresh fruits and vegetables, their ties to the neighborhood and their willingness to extend credit.

3. Strong Domestic Players in a Fragmented Retail Sector

Turkey’s modern (or organized) retail segment is led by domestic players, which create a highly competitive market where international firms’ penetration is very low. We define “modern retail” as the segment of the industry composed of players that operate chain stores that are all owned or franchised by a central entity. The segment is highly fragmented in Turkey and accounts for 60% of the total retail sector, according to Global Source Partners.

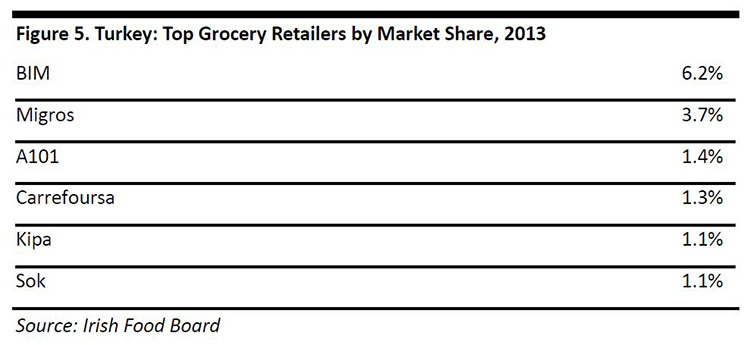

The top six grocery retailers in Turkey held just 14.8% of the grocery retail market in 2013, according to the Irish Food Board. Of these, the top three are domestic retailers, and, as of 2016, only one, Carrefoursa, is partly owned by a foreign group.

Discounters Lead Grocery Retail

Of the top six grocery retailers in Turkey, three—BIM, A101 and Sok—are discounters. The discounters’ share of modern grocery retailing in Turkey exceeds their peers’ share in Germany, which we refer to as “Discountland” in our May 2016 report German Retail Overview—this report can be found at bit.ly/FungGermanRetail

According to Kantar Retail, discounters accounted for 41% of modern grocery retail in Turkey in 2013 and for 33.8% of total retail. In Germany, discounters accounted for 40.1% of modern grocery retail in 2015, according to Euromonitor data. This compares with single-digit shares for discounters in other mature markets, including France, the UK and the US.

Discount is also the fastest-growing grocery sales channel in Turkey. According to Kantar, discounters will account for 44.0% of grocery retail by 2018, growing at a CAGR of 19.6% from 2013 through 2018. The channel is growing at the expense of supermarkets, hypermarkets and traditional grocery retailers.

Discounters have been able to rapidly expand because they meet three primary needs of Turkish consumers: they provide proximity shopping, one-stop shopping and low prices.

- Proximity shopping: Discounters tend to have two advantages over other kinds of modern retailers: the average size of discount stores is smaller than the average size of supermarkets and hypermarkets, and discount stores tend to be located in urban areas with high population density. BIM, the leading discounter in Turkey, operates stores that are about 350 square meters (3,767 square feet) in size.

- One-stop shopping: Consumers shopping at local discounters have the convenience of finding a wider range of products in one place than they would find at independent neighborhood grocery stores. While bakkals also offer the convenience of proximity shopping, their limited size—about 50 square meters (538 square feet) or less, on average—means they can stock only a limited range of SKUs.

- Low prices: Of course, the main selling point of discounters is their low prices compared to other channels, and Turkish consumers tend to be price sensitive, according to export promotion agency Export Finland.

How Other Grocery Retailers Have Responded to Discounters

Confronted with the growth of discounters such as BIM, other modern grocery retailers have reacted by offering larger product ranges, more fresh food, more brands and private labels, competitive pricing, and more ways to shop through different store formats.

- Larger product portfolios at competitive prices: In comparison to BIM, which carries about 600 SKUs, nondiscount grocery retailers offer many more SKUs, including fresh products. Migros, for instance, boasts a range of thousands of SKUs and private labels, while Carrefoursa offers 50,000 SKUs. In 2015, it enhanced its range of fresh food at accessible prices. Larger product portfolios should encourage one-stop shopping by making it easier for consumers to find everything they need in one place, while private labels and price-matching policies should attract consumers who are more price sensitive. According to the Migros’s 2015 annual report, competitive pricing was instrumental in allowing the company to reach a wider consumer audience during the fiscal year.

- Expansion of convenience-store formats: In comparison to BIM, which operates mainly through small neighborhood stores, nondiscounters have a larger variety of store formats, designed to capture different segments of the consumer base. Migros trades in Turkey through six banners, while Carrefoursa and Kipa have four formats each. Many nondiscount retailers have opened smaller store formats to better respond to Turkish consumers’ demand for proximity shopping. Migros has operated Migros Jet convenience stores since 2010, and Carrefoursa and Kipa run the Mini and Ekspres banners, respectively.

Even as nondiscounters have moved to counter the discounters’ growth, Turkish discounters have diversified from their core business model to include more fresh food, bakery and enhanced customer service, adding further competitive pressure to other retailers. For instance, in 2015, BIM launched FILE, a new banner that offers larger stores, a wider product range that includes patisserie, meat-charcuterie, fresh food and personal care, and that focuses more attention on customer service and outlet aesthetic. With FILE, BIM aims to gain further share of the grocery market at the expense of nondiscount retailers.

Domestic Firms Also Lead Nongrocery Retail

While grocery is the main retail sector in Turkey, other segments are worth considering in terms of their size and dynamism, particularly the apparel and footwear and consumer electronics segments.

Similar to the grocery segment, the apparel and footwear segment in Turkey is characterized by fragmentation and the presence of strong domestic players. However, international fast-fashion retailers have expanded dynamically in the country.

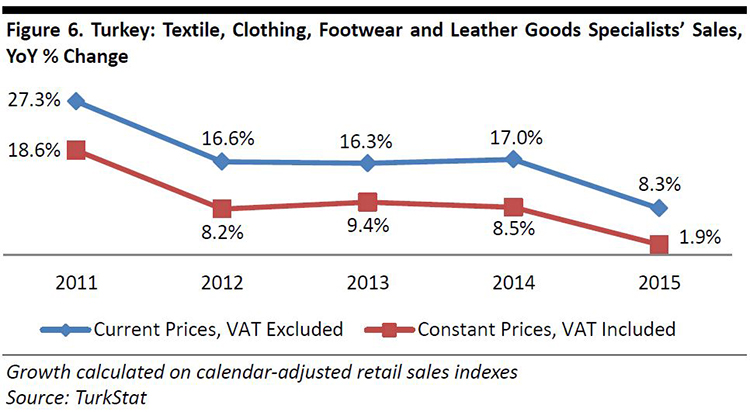

Turkish consumers show a strong propensity to spend on apparel and footwear and it is one of the fastest-growing retail categories in retail in Turkey. Consumer expenditure in the category grew at a CAGR of 15% from 2009 through 2014, reaching TRY3.1 billion (US$1.4 billion) in 2014, according to TurkStat. The statistics agency estimates that clothing and footwear specialists’ sales grew at a CAGR of 17% (in current prices) from 2010 through 2015, making clothing and footwear specialty retail the fastest-growing channel after e-commerce. Deloitte estimates that the Turkish clothing and footwear sector will reach a total value of US$37 billion by 2018.

However, despite the category’s overall growth in recent years, year-over-year sales growth slowed between 2012 and the end of 2015, in response to slower economic growth and a deterioration in consumer confidence.

Domestic apparel and footwear retailer Waikiki leads the sector. The retailer operates in Turkey and in a number of other markets, including Russia and other economies in Central Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa. In 2013 (latest), Waikiki generated US$2.5 billion in global revenue, while its share of the Turkish market was 16.5%, according to company reports.

Waikiki’s leading position is due to its strong presence, competitive pricing and diverse range of clothing. It is one of the best-established retailers in the market and enjoys strong brand awareness among consumers. The company has more than 400 stores in Turkey and targets budget-conscious shoppers. The brand caters to the wardrobe needs of a broad range of people, from fashionable young people to more conservative middle-aged customers. Waikiki was initially a French brand; it started to source garments from Turkey and was then purchased by Turkish entrepreneurs in 1997.

Unlike in other retail segments, where international companies have been gradually disengaging from Turkey, in apparel, international fast-fashion chains have been expanding. Turkey has a relatively young population with westernized tastes in fashion, especially in Istanbul and other large cities. This creates a favorable environment for international fast-fashion retailers.

From 2010 through 2015, Spanish apparel retailer Inditex expanded its store network in Turkey by 77 units. By January 2016, it was operating 191 stores in the country. Inditex has a brick-and-mortar presence in the market for all but two of its concepts. The retailer is planning to extend online operations in Turkey for all its brands during 2016. Turkey is also a very important sourcing hub for Inditex, which sources from countries with geographical proximity to its main European markets to ensure speed to market.

Swedish fast-fashion retailer H&M entered the Turkish market in 2010. For fiscal year 2015, the company reported Turkish sales of SEK2.2 billion (US$260.9 million), a year-over-year increase of 65.5% in reporting currency, and expanded its store network in Turkey by 16 units. By November 30, 2016, H&M had a total of 46 stores in Turkey.

Inditex and H&M’s numbers reveal that these international fast-fashion retailers are expanding significantly in the Turkish market, despite the strength of domestic companies and an economic slowdown.

We believe that the positioning of these international retailers benefits them, as they do not compete directly with strong domestic players. Waikiki, for example, caters to a broader consumer base that includes more conservative, older consumers living in second-tiers cities, while Inditex and H&M target primarily younger, aspirational and fashion-conscious urban consumers who seek internationally recognized brands.

Turkey has a relatively young population and has seen rapid urbanization, making it an appealing market for consumer electronics retailers. Sales of products such as smartphones have been growing rapidly. According to market research agency eMarketer, the number of smartphone users in Turkey grew by 38% year over year in 2014, to 22.1 million (about 30% of the population), and the firm expects the number to reach 48 million by 2019.

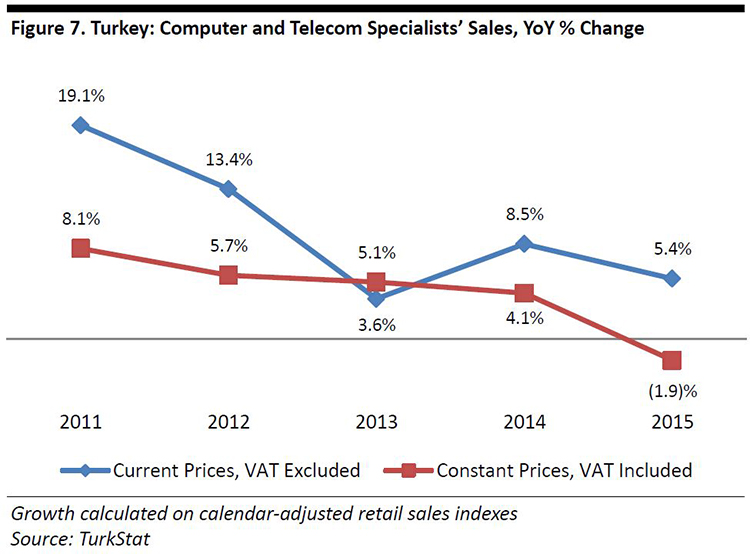

Sales by IT and telecoms specialist stores grew at a CAGR of 10% in current prices from 2010 through 2015, according to TurkStat. The total value sales of consumer electronics and technological goods in Turkey exceeded US$16 billion in 2013, according to Deloitte. However, similar to apparel, year-over-year growth in consumer electronics sales slowed in the period from 2011 through 2015.

As with other main retail sectors, consumer electronics retail in Turkey is characterized by fragmentation and by the lead of domestic players, including Teknosa, Bimeks, Vestel, Vatan Computer, and Koç Holding’s retail banners, Arcelik and Beko.

Teknosa, with an 8% share of the market, is the leading player in consumer electronics and white goods retailing in Turkey, according to company reports. The company generated TRY3.2 billion (US$1.2 billion) turnover in 2015, an increase of 5% year over year. Teknosa maintains its leading position thanks to its:

- Extensive presence: The company had 278 stores nationwide as of the end of 2015, and a presence in 78 cities.

- Multi-channel retailing: The company operates an online shopping platform, Teknosa.com, and click-and-collect operations.

- Pricing: The company offers competitive pricing and makes extensive use of promotions and loyalty programs (a loyalty card was introduced in 2008).

- Services: The retailer offers basic services ranging from installation to technical support and has also introduced additional services, such as Teknosa Mobil, a mobile telecom service launched in February 2015.

- Private-label tech products: In 2015, the company introduced its private-label smartphone and smartwatch brands, Preo P1 and Preo Pwatch, in a bid to provide customers with the latest technology at an affordable price.

German retailer Metro Group, through its Media Saturn operation, is the most notable international company with a presence in the Turkish consumer electronics sector. The company entered the market in 2007, when it opened a Media Markt store in Istanbul. As of September 2015, Media Saturn had 41 stores in Turkey, mainly concentrated in the largest cities. In its 2015 annual report, Metro commented that its consumer electronics retail business in Turkey had proven extraordinarily robust, achieving solid double-digit growth.

Domestic players leverage their strong presence and brand recognition to gain competitive advantages over foreign retailers. As in other markets, a strong brick-and-mortar presence is particularly important in consumer electronics retailing in Turkey, as store personnel can provide pre- and after-sales customer service that is highly valued by consumers, especially those unfamiliar with technology devices. In this sense, companies such as Teknosa, which has 278 stores versus Media Saturn’s 41, have a clear competitive advantage.

Locals Consolidate While Internationals Disengage

Turkey was particularly attractive to international retailers during the country’s period of economic growth that began in 2002. However, foreign retailers soon found that, despite the apparently favorable environment, it was very difficult to succeed without the support of a domestic partner, in part due to strong domestic competition. A lack of transparency in regulations was another factor: the World Bank and the US Department of Agriculture are among the institutions to have noted the unpredictability and complexity of Turkish regulations.

As the Turkish economy began slowing 2012, a number of international retailers started to disengage from the market, ceding their stakes to their local partners or selling their operations to domestic competitors. In 2013, the number of international companies that disengaged from the Turkish market was particularly high.

- In grocery, Carrefour ceded majority control of Carrefoursa to its Turkish partner Sabanci Holding, selling part of its stake to the Turkish firm. Also, Spanish discounter DIA sold its stake in its local subsidiary DiaSA to Turkish conglomerate Yildiz Holding.

- In home improvement, German retailer Praktiker closed its stores in Turkey, as they were loss making. French retailer Leroy Merlin, which entered the market in 2010, announced its exit in January 2014.

- In consumer electronics and appliances, British retailer Dixons Retail (now Dixons Carphone) sold its loss-making Turkish ElectroWorld operations to domestic electrical-goods specialist Bimeks. This came after US electronics retailer Best Buy sold its Turkish operations to Teknosa in 2011.

More recently, in December 2014, Anadolu, a Turkish conglomerate, agreed to buy a stake in leading nondiscount grocery retailer Migros from UK-based private-equity firm BC Partners. Anadolu bought half of the 80.5% stake that BC Partners had acquired in 2008 from Turkish group Koç Holding, which had owned the retailer since 1975. Migros was originally the Turkish operation of Swiss grocery retailer Migros, which entered the market in 1954.

British retailer Tesco is the most recent international player to exit the Turkish market. On June 10, 2016, the company agreed to sell its Turkish operation, Kipa, to Migros for about US$43.5 million. Migros is planning to divest the retail banner’s larger store formats and expand its smaller store formats, as Kipa’s overreliance on the former was one of the reasons the chain was loss making.

International retailers’ disengagement is fueling Turkish players’ consolidation strategies, and domestic companies are using acquisitions to scale up their businesses.

E-Commerce Has Room to Expand Further

Turkey has shown mixed progress when it comes to digitalization.

- Internet penetration is still relatively low: Currently, only 58% of the Turkish population has access to the Internet, according to estimates from Internet Live Stats; this compares to 88% in Germany.

- Mobile Internet usage is relatively high: Turkey has more than 73.8 million mobile subscribers and 41.9 million mobile Internet users (a penetration rate of 53.6%), according to first-quarter 2016 figures from the Turkish Information and Communication Technologies Authority. This compares with 56.5% mobile Internet penetration in Germany, according to eMarketer.

- Social-network penetration is high: According to marketing agency We Are Social, as of January 2016, active social-network penetration was 53% in Turkey, higher than in France, Italy and Spain.

Turkey is delayed in certain aspects of digitalization, which means its e-commerce market lags that of most other developed countries. E-commerce’s share of total retail was only 2% in Turkey in 2015, versus 7.1%, on average, in developed markets, according to the Turkish Informatics Industry Association (TUBISAD).

However, Turkey’s relatively high rates of mobile Internet and social-network use, combined with a young and growing urban population, make it an environment conducive to growth: e-commerce grew by 31% year over year in 2015, to TRY24.7 billion (US$9.1 billion), according to TUBISAD.

In terms of the competitive environment, Internet retailing in Turkey is characterized by the lead of local players, as are other retail channels. This mirrors the situation in China, where international firms such as Amazon are confronted with strong domestic players and, to some extent, a hostile business and regulatory environment. But unlike in China, e-commerce in Turkey is also characterized by high fragmentation, as are other retail segments in the country.

Domestic firm Hepsiburada, the leading e-commerce pure play, has a market share of 15%, according to the Abraaj Group, a private-equity firm that acquired a 25% stake in the company in February 2015. The Istanbul-based company was established in 1998 as an IT hardware online retailer, but soon started to diversify its portfolio. As of 2015, it had a product range of more than 500,000 items across 30 categories. Today, consumers can buy anything from food to clothing to smartphones to cosmetics on Hepsiburada.com. The company is majority owned by Turkish conglomerate Dogan Group, which bought it in 1999.

Hepsiburada has been referred to as the Amazon of Turkey. It is the leading e-commerce retailer in its domestic market, as Amazon is in its own. It shares other striking similarities with Amazon, too, including:

- Early entry advantage: Similar to Amazon, the company was established in the second half of the 90s, at the dawn of Internet retailing.

- Multi-category retailer: On Hepsiburada’s site, consumers can buy anything from food to clothing to smartphones to cosmetics.

- Third-party marketplace: The company is both an online retailer and an online marketplace for third-party retailers.

- User experience: Hepsiburada provides value-added services such as same-day delivery and express checkout; it is Turkey’s only online retailer with the requisite infrastructure to store credit-card data.

- Logistics: The company has a strong logistics infrastructure in Turkey. It used funds from Abraaj’s investment to build a new, 100,000-square-meter fulfillment center.

Among international e-commerce pure plays, US-based eBay is the only one with a significant presence in Turkey. The company trades in the country through the GittiGidiyor online marketplace, in which eBay acquired a majority stake in 2011. GittiGidiyor was launched in 2001 as a Turkish equivalent to eBay.

Leading brick-and-mortar retailers in Turkey dipped their toes into e-commerce and multi-channel retailing early, and they continue to implement strategies to take advantage of the growth in e-commerce. Migros and Teknosa provide two illustrative examples:

- Migros introduced Migros Virtual Market, an online grocery-shopping portal, in 1997. Since then, the retailer has extended its multi-channel provision with services such as Buy When Passing, which allows customers to collect grocery purchases from partner gas stations, and by installing online shopping kiosks in stores.

- Teknosa launched its transactional website in 2003 and started offering click-and-collect from its stores in 2014. Online sales in 2015 increased by 44.2%, to TRY437 million (US$161.1 million).

- Given that e-commerce still accounts for only a small share of overall retailing in Turkey, there is plenty of room for further growth, such as the expansion of multi-channel options by brick-and-mortar retailers.

RETAIL IN CONTEXT: ATTEMPTED COUP CAUSES DISARRAY

In this section, we place the retail sector in context, with a discussion of macro indicators such as economic growth, and a consideration of recent turmoil within Turkey.

Economic Growth Outpaces that of Western European Nations

Underlying uncertainty has been eroding Turkey’s economic growth and consumer confidence in recent years. The country was hit by a severe financial crisis in 2001, caused by a rapid fleeing of international investors worried about political and economic instability. This left a vacuum in capital that Turkish banks—which were holding a massive amount of sovereign bonds that the government was not able to pay off—could not fill.

In response to the 2001 recession, Ankara adopted financial and fiscal reforms as part of an International Monetary Fund program, which strengthened the country’s economic fundamentals and led to an era of strong growth.

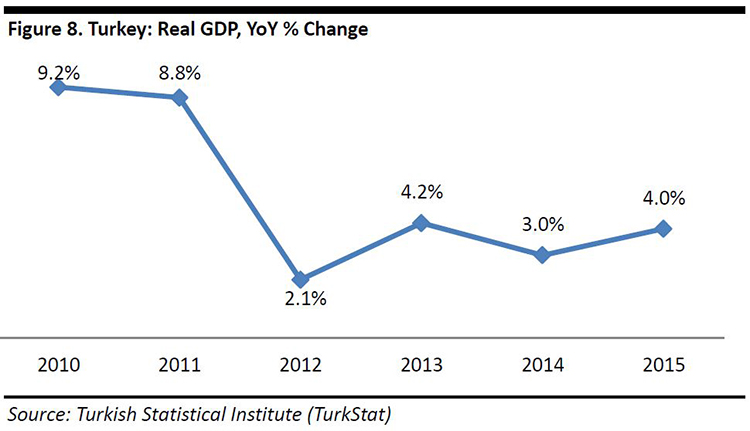

However, in 2012, economic growth slowed by 670 basis points due to internal sociopolitical tension and regional geopolitical turbulence. The eurozone crisis exacerbated the situation, as Turkey is largely dependent on Europe for its exports and for foreign direct investment. The recession in Russia, an important commercial partner for Ankara, combined with worsening bilateral relations between the two countries, also contributed to the volatility of the Turkish economy.

Nevertheless, the economy showed resilience and accelerated in 2013, even amid concerns about high inflation and the volatility of the Turkish lira against major currencies.

Prior to the recent coup attempt, the country’s annual GDP growth was projected to remain close to 4% in 2016 and 2017, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). To place this in some context, in 2015, Eurostat recorded real GDP growth of 2.2% in the UK and 1.7% in Germany.

Young and Growing Population with Propensity to Spend

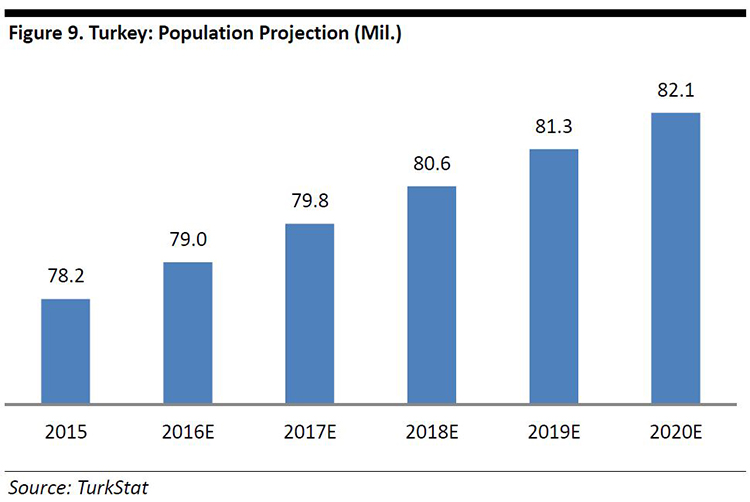

Turkey’s demographics add to its appeal for retailers. The country has a large population, numbering 78.2 million in 2015, almost equal to Germany’s. But the Turkish population has also been growing relatively fast, at 1.2% per year, on average, from 2010 through 2015, according to TurkStat, and it is expected to continue to grow at an average of 1.0% through 2020. By comparison, the population of Germany declined marginally, by an average of 0.1% per year, in the five years through 2015, according to Eurostat data.

In addition, Turkey’s population is relatively young. The average age of the country’s population is 30.1, which is 16.4 years younger than the average person in Germany, according to the CIA’s World Factbook.

Turkey shows high rates of urbanization and increase in population density. Istanbul, a city of 14 million people, has a population that is growing at a rate of 3.45%, which makes it one of the fastest-growing megacities in the world, according to Forbes.

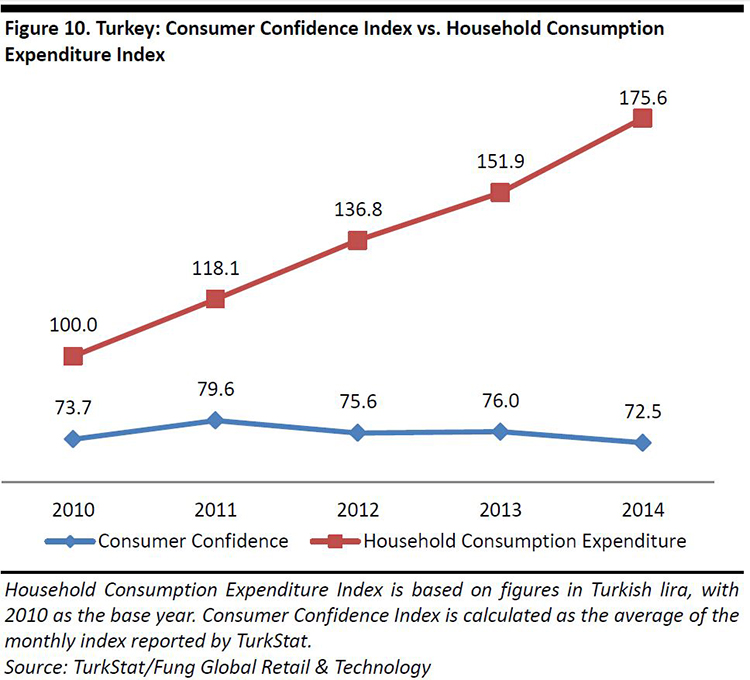

Consumer expenditure is another indicator that showed resilience to the economic uncertainty that began in 2012. Household consumption expenditure grew very rapidly—at a CAGR of 17.5%—in the period of sustained economic growth from 2002 through 2009. But even when the economy started to slow down in 2012, Turkish consumers kept spending: household consumption expenditure continued to grow substantially, at a CAGR of 15.1% from 2010 through 2014, according to data from TurkStat, despite a weakening of consumer confidence.

In the subsequent sections, we turn to the recent upheavals in Turkish society and politics.

Background to the July 2016 Attempted Coup

In the recent past, Turkey has been buffeted and challenged by a series of domestic traumas. These include shootings and bombings by ISIS, such as at Istanbul airport on June 28 and at a wedding in southeastern Turkey on August 20; violence from Kurdish PKK terrorists; and an attempted coup by elements in the Turkish armed forces on July 15. The coup failed, but there was a great deal of bloodshed by the coup plotters, who almost succeeded in killing President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

As the coup attempt was under way, hundreds of thousands of Turks took to the streets and confronted the military at the behest of the government. This popular support by civilians in large part caused the attempt to fall apart.

Since the coup attempt, thousands of soldiers, judges, academics, journalists, media staff and others have been detained, imprisoned and/or forced to resign their posts. Universities, newspapers, charitable foundations and other institutions have been closed, and their assets seized. More than 1,500 academic deans have been forced to resign, and academics are prohibited from traveling abroad. Erdogan declared a three-month state of emergency on July 20, and Turkey’s Parliament approved it on July 21, giving Erdogan authority to rule by decree. After the coup attempt, Turkey revoked its participation in the European Convention on Human Rights and announced its intention to reintroduce the death penalty. The changes will likely lead to diminished human rights in Turkey.

Some Turkish political leaders have accused the US of organizing the attempted coup. Such claims have been firmly denied by US Secretary of State John Kerry as well as by US Ambassador to Turkey John Bass.

Turkey has accused a preacher living in Pennsylvania, Fethullah Gulen, of masterminding the coup, and has sought his extradition from the US to Turkey. The US response from President Barack Obama and Secretary of State Kerry has been that the US is required to follow certain legal procedures under the extradition treaty between the US and Turkey. The legal process could take years to resolve.

Political Leadership

Erdogan’s party, the Justice and Development Party (AKP), won the national Parliamentary elections in November 2015, achieving a majority in the Parliament. Both the president and prime minister of the country are members of the AKP; Erdogan was elected president in 2014 for a five-year term and Binali Yildirim is currently the prime minister. While the prime minister technically and legally holds power, Erdogan has turned the historically ceremonial post of president into a very powerful position. Even before the attempted coup, Erdogan had significant control over many political functions, such as the military and intelligence. In the wake of the coup attempt, Erdogan’s power and influence have increased; with the state of emergency, the revocation of the European Human Rights Convention and the removal of thousands of judges, as well as other actions, the president now wields much more power.

The AKP has been in power since 2002, except for a brief period between June and November 2015, when it lost its majority to the opposition parties. The principal opposition parties in the Turkish Parliament are the Republican People’s Party (CHP), the secularist party in the spirit of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, founder of the Republic of Turkey; the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP); and the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), the Kurdish party in Parliament.

It is of particular note that the AKP and Erdogan have accused the HDP of being a terrorist organization affiliated with the PKK Kurdish terrorist group, and have sought to remove HDP Parliament members’ immunity from prosecution, a right ordinarily held by all members of the Turkish Parliament. One of Erdogan’s goals has been to have the AKP achieve enough votes in Parliament so that he could legally assume the status of a “super-president,” with enhanced powers. This has eluded him to date because the AKP could not garner sufficient votes in Parliament. As a result of the attempted coup and state of emergency, however, Erdogan now has, in effect, achieved such a super-presidency.

Turkey’s Kurdish minority numbers more than 14 million and has complained of not being allowed to develop the Kurdish language and culture. The PKK Kurdish group has been at war with the Turkish military and civilians for many years, and has killed thousands, including innocent civilians. There was a brief hiatus in hostilities between 2013 and 2015, when the Turkish government and Kurdish leader Abdullah Ocalan engaged in a peace process, but the process fell apart in 2015 and attacks and counterattacks between the Turkish government and the PKK resumed.

About 73% of the Turkish population is Sunni Muslim and about 25% is Alevi (Alevism is an offshoot of Shiism). The population at large is divided between more-religious Turks, most of whom are aligned with Erdogan’s AKP, and other groups, including secular Turks and Kurds. Many religious Kurds support the AKP.

Implications of the July 2016 Attempted Coup

In light of the attempted coup, the future in Turkey cannot be predicted with any degree of certainty. The actions of the three major credit-rating agencies underscore this:

- Following the coup attempt, S&P lowered Turkey’s foreign currency rating from BB+ to BB, nudging it further into speculative or “junk” status. S&P stated that “the negative outlook reflects our view that Turkey’s economic, fiscal and debt metrics could deteriorate beyond what we expect, if political uncertainty contributed to further weakening in the investment environment, potentially intensifying balance-of-payment pressures.”

- Moody’s put Turkey on review for a possible downgrade as a result of the coup attempt. Currently, Moody’s rates Turkey’s credit at Baa3, the lowest level of investment, according to Bloomberg. “Both Moody’s and Fitch were a bit premature in upgrading [Turkey’s rating] to investment grade,” according to Win Thin, Global Head of Emerging Markets Strategy at Brown Brothers Harriman, a financial-services firm. “Deteriorating fiscal and external balances, coupled with worsening political risk, are likely to be the triggers for a downgrade this year,” Thin noted, according to Bloomberg.

- Fitch Ratings said that the attempted coup and the authorities’ reaction to it “highlight political risks” to Turkey’s BBB- rating. The company further stated that the “political fallout” from the coup “could refocus attention on Turkey’s large external financing requirement if it results in significantly diminished international investor confidence.” Fitch’s next rating review is on August 19.

Turkey’s current account deficit is the Achilles heel of its economy. The Turkish lira is down appreciably, and growth had slowed even before the coup attempt. This makes it unlikely that Turkey will be one of the top 10 countries in terms of GDP by 2023, the 100th anniversary of its founding—despite the government having announced that as a goal.

Also, prior to the coup attempt, tourism had fallen substantially due to recent attacks; the coup attempt struck a further blow to the industry.

The consideration of Turkey’s accession to the European Union (EU) has been in play for years, with Germany and France the leading opponents of it. The EU leadership has informed the Turks that the reimposition of the death penalty in the country and its revocation of the European Convention of Human Rights are not acceptable and will affect Turkey’s chances of joining the EU.

Furthermore, opinion polls from the Pew Research Center show extreme antipathy in Turkey for the US, the EU and the West in general. This sentiment is likely to increase, as the US has been blamed for the coup attempt. Erdogan has criticized the EU for holding prejudiced attitudes against Turks. We judge the chances for Turkey’s EU accession as zero, given the foregoing factors; so long as they remain consistent, we think Turkey will not be able to join the EU.

Gulen Extradition Request and Its Impact on US-Turkey Relations

The likelihood is very low that the US will extradite Gulen to Turkey to stand trial in the near future. As a US green card holder, Gulen is entitled to US constitutional rights, and the Turks need to provide solid proof of his involvement in the coup attempt before the US will extradite him. Already in Turkey, institutions seen as having ties to Gulen have been closed and their assets confiscated, and Gulen’s nephew and an aide have been arrested.

The Turkish government has suggested that the US’s failure to extradite Gulen will affect US-Turkish relations. We may even see a breakdown in relations that will imperil the existence of the US air base in Incirlik, which has been the launching point of the coalition war against ISIS in Syria. During the coup attempt, electrical power to Incirlik was cut off, and the Turks have claimed that tanks and other equipment from the base were used in the coup attempt. Some 50 nuclear weapons (hydrogen bombs) are kept at Incirlik.

Turkey may reach out to Russia and China as an alternative to maintaining close relations with the US. Russia is an important source for Turkey’s energy needs. As for China, Turkey had a dalliance with a Chinese company, CPMIEC, from which it considered acquiring missiles (these, incidentally, were not interoperable with North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) equipment, causing great consternation in the US defense industry, which traditionally has provided missiles to Turkey). Ultimately, the Chinese deal did not go through.

Relations between the US and Turkey are likely to continue to be strained, and Turkey’s forming close relationships with Russia and China will only exacerbate the situation. Furthermore, Turkey’s future status in NATO is in doubt and Turkey may join the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (of which China and Russia are key members) as an alternative.

Western Intervention in Turkey’s Internal Affairs Unlikely

The US government, as well as the current candidates for US president, have taken a hands-off approach regarding the recent events in Turkey. Obama and Kerry want to keep Turkey on board in the war against ISIS and also maintain full access to the coalition’s base of operations at Incirlik. As mentioned, Turkey is also a current member of NATO.

Donald Trump, the Republican Party nominee for president, commended Erdogan for turning the coup attempt around and believes in “America First,” a policy of staying out of the affairs of other countries. Hillary Clinton, the Democratic Party nominee, is also unlikely to take any action against Turkey if she becomes president, as she recognizes Turkey’s importance in NATO and in the war against ISIS.

The Turkish government announced the reorganization of the military, which may leave Turkey open to more violence from the PKK and ISIS, which would further destabilize society.

Thousands of Turks have been fired, arrested and/or detained. The actions against academics will result in utter confusion when the academic year begins shortly. Some have even predicted that Turkey will suffer a “brain drain,” whereby academics will flee the country for other locales—although, at this point, academics are not permitted to travel abroad.

In addition, there is a literal schism in society between secular and religious Turks, which could lead to civil war. Unless this and the above-mentioned factors change, there will be continued instability in Turkey.

Impact on Retail

The Turkish economy and society are in disarray, but the government’s stated intention is to continue business as usual. It is unclear how this can occur, though, as Turkish citizens lack confidence in the future of the country and international investors worry about the risks of doing business and employing capital there.

At the time of writing, there are few economic, consumer or company data points available for August, the first full month after the coup attempt. Two metrics that have been published by TurkStat are the consumer confidence and economic confidence indices:

- Counterintuitively, consumer confidence was up solidly month over month and year over year, to a level of 74.4 in August. It had previously declined slightly month over month, from a level of 69.4 in June to 67.0 in July.

- The economic confidence index, however, which factors in consumers’ and producers’ sentiment on the general economic situation, slumped month over month and year over year in August: the metric was down by 2,300 basis points month over month and down by 1,380 basis points year over year. All business sectors reported declining confidence month over month.

There is little doubt that the retail sector will have been impacted significantly in July and August. The downturn in tourism, the attacks on civilians and the attempted coup have resulted in empty streets and significantly diminished consumer activity in important locales such as the Taksim area in Istanbul. The retail sector in Turkey will certainly suffer unless the economy—and investor and consumer confidence—get back on track quickly and with strong effect.

In summary, these are the changes we will likely see in Turkish retail in the coming years:

- There is still substantial penetration potential for modern retailing, as 40% of the retail market in Turkey is still operated by smaller independents.

- Domestic retailers will likely consolidate their lead of the retail sector following recent waves of disengagement by international retailers.

- The retail sector will likely become more concentrated, with leading companies such as BIM and Migros scaling up their businesses and further expanding their market shares.

- International retailers that still have operations or stakes in Turkey may consider further disengagement, while potential new entrants may be further discouraged from accessing the market in light of recent political events.

- Turkish retailers could further expand outside Turkey. BIM already operates stores in Morocco and Egypt, while Migros has a presence in both Kazakhstan and Macedonia. Additional consolidation in Turkey might encourage these two retailers to seek further expansion abroad.

- Given its relatively low share of the retail market, e-commerce shows room for future expansion. Turkey has a young population that is comfortable using social media and the mobile Internet. Leading pure plays such as Hepsiburada are expected to strengthen their market shares, while brick-and-mortar retailers such as Migros and Teknosa are likely to further expand their multi-channel operations.

Overhanging all of these industry-specific shifts is the heightened political, societal and economic uncertainty in the country. Turkey now has to deal with the fallout from the July 2016 attempted coup—and the full shape and effects of the post-coup response have yet to fully emerge. We therefore reiterate our view that the future in Turkey cannot be predicted with any degree of certainty.